“Do you love my insides? The parts you can’t see?”

Drusilla asks Spike this question early in the episode, and it lays out the theme pretty clearly. This is an episode about hidden selves, about duality. It’s about taking a look at the characters’ Inner Selves – the parts we can’t see – and comparing them to their outward presentations – the parts we can. We are invited to consider whether the Inner Self is something that should be loved and celebrated, or hidden away for the good of others. And we should compare that to the image that these characters present to the world – the costumes that they wear.

The costume, in this case, is the Outer Self – the version of ourselves we present to the world. This can be a reflection of the Inner Self, or a means to hide it – or somewhere in between. One of the most basic questions about humanity is which of these Selves is the “true” self? Are we what we do? Are we the person others see? Or are we what we are inside? These are questions far too big and esoteric for a Buffy the Vampire Slayer blog to answer, but Halloween does scratch at their surfaces in some interesting ways.

In two very specific ways, I think. First, through the idea of costumes as concealing a hidden sef, and secondly the idea of costume as gender performance. Two different ways of interacting with and expressing the Inner Self, and two lenses through which we will look at this episode.

Part One: Willow, Giles, and the Hidden Self

“What does this mean?”

Willow Rosenberg and Rupert Giles, 2×06 Halloween

“Primarily, the division of self. Male and female, light and dark.”

Both Willow and Giles use costumes in this episode as a disguise – a veil to cover some part of themselves. In both cases, the urge to do this stems from some kind of shame.

Carrying on her costume motif that started in Inca Mummy Girl, Willow actually gets two costumes. First, the full-sheet Ghost costume that she picks out for herself. Second, the generically “Sexy” outfit that Buffy picks out for her.

Willow is somebody who is consistently anxious over how she presents, and how others see her. Her dream in Restless digs most deeply into this idea, but it’s already here in this episode. Both her costumes are insufficient representations of her true self. Buffy describes the Ghost costume as “hiding”, and we see that is accurate, when Willow is visibly nervous about being seen in more revealing clothes, and so reverts to the sheet ghost mainly because it’s easier. However, she also describes the Sexy costume as “not me”, and that’s accurate too – we never see Willow in this style again, because it’s not an accurate reflection of her internal self.

It is significant that when Ethan’s spell hits, she becomes both costumes. She becomes the Sexy Ghost. It is not the case that one of these costumes is her “true” self and the other is a way to cover up. They’re both cover-ups. Neither of these costumes are fully Willow, but simply different images that she can project. They are both mere symptoms of her insecurity, of her self-directed shame.

“Look, Halloween is the night that not-you is you. But not you. Y’know?”

Buffy Summers, 2×06 Halloween

Buffy lays out the lesson that Willow needs to learn this episode. She is fretting so much about how others perceive her, not realising that the way she is perceived does not define her. Just because she puts on a certain costume, that doesn’t change who she is. But in order to learn this, she first needs to be literally magically changed.

This is one of Willow’s finest episodes so far, in terms of how impressively she takes control of the situation. This is just like what we see in Anne, and later Bargaining. In the absence of Buffy, Willow takes control. She steps into her role and leads the group. She is able to do this because she is forced to take on the aspects of her costume, and so she stops worrying about them. She becomes the Sexy Ghost, and therefore is able to realise that she is not the Sexy Ghost. She is Willow – and Willow is strong, confident, and able to lead in a crisis.

Early in the episode, we see Oz talking to Cordelia, and he sardonically grumbles about how he can’t meet a “nice girl”. He turns around, and bumps into Willow – the very nice girl he saw and was interested in before – but this time, he doesn’t notice her. She’s in the Ghost Costume, hiding her face from view. Willow’s shyness clearly inhibits her otherwise very strong chance at romance.

When she drops the Ghost costume at the end of the episode, and walks assuredly down the street, it’s not because she has fully embraced the Sexy costume. It’s because she’s gained enough confidence in herself that she no longer needs to hide. She’s is able to be “not-her”, because she recognises and likes who she is a little bit more. And so this time, Oz notices her. When he asks “who is that girl?”, repeating his catchphrase from before, the answer is clear. It’s Willow.

We all know where the Willow story is heading. There is not much exploration of it specifically in this episode, but we all know that Willow has a dark side. It is a side to her that she, at various points, tries to keep hidden or to intentionally display to the world, depending on what end she wants to achieve. She will struggle to understand this part of herself and incorporate it into her self-perception. Luckily, she has Giles to help her with that. As we are just about to find out, Giles has his own dark side, and understands quite well how that reflects on a person’s identity.

“Do you want to be punished?”

Rupert Giles and Willow Rosenberg, 7×01 Lessons

“I wanna be Willow.”

“You are. In the end, we all are who we are, no matter how much we may appear to have changed.”

Giles is not able to make such a peace with his own duality in this episode. He is the only member of the core four Scoobies who doesn’t get his own costume in this episode – because it is revealed that he’s been wearing a costume the entire time; the costume of the mild-mannered librarian Rupert Giles. At least, that’s Ethan’s interpretation.

“Oh, and we all know that you are the champion of innocents and all things pure and good, Rupert. It’s quite a little act you’ve got going here, old man.”

Ethan Rayne and Rupert Giles 2×06 Halloween

“It’s no act. It’s who I am.”

Later installments like The Dark Age and Band Candy will expand on it further, but this is our first sighting of Ripper – Giles’ hidden dark side. Ripper is all the parts of Giles that he feels shame over, and wishes to hide. His recklessness, his immaturity, his calculating coldness, his lack of regard for the safety of others. These are all things that feel very unnatural for the Giles we have known up to this point, yet they are all absolutely a part of him.

There is a heavy emphasis early in the episode on Giles’ stuffiness, to the point that he actually references “cross-referencing” as a relaxing hobby. It’s a solid note, but it shows how one-dimensional a character Giles could have remained, if this backstory had not been introduced. This is the point where we really start to understand Giles as a complex and deeply flawed character.

The question that Ethan Rayne poses is a simple one: who is Rupert Giles? Is he the “tweed-clad guardian of the slayer”, that we have known up to this point? Or is he this “Ripper”, the stranger who so casually breaks a man’s face with his fist? Which is the Self and which is the Costume? Ethan seems pretty convinced that the former is merely a costume that the latter wears. Giles himself disagrees, and insists that the former is who he is. In his eyes, the Ripper image is a costume that he puts on, for the practical purpose of intimidating Rayne into revealing how to break the spell.

So which one is true? The answer, of course, is both, and neither. Both are a part of Rupert Giles’ life, shaping him into the man know today. Both are images that he projects for different specific purposes. All must be considered as a valid part of the Self. To paraphrase Giles himself – he is who he is, no matter how much he appears to change. He is like Buffy, with her Slayer and Girl sides. Or Willow and Dark Willow. Or, especially pertinent to this season, Angel and Angelus.

Angel is a character defined by his duality, and his contradictions. He is a vampire with a soul, a great Champion and terrible Villain. The question that defines him is very similar to the one posed around Giles in this episode. Is he a man who sometimes looks like a monster, or a monster that sometimes looks like a man?

This tension is given form with “vamp face” – the features that are either his true face, or the mask he wears. This is his costume this episode. We will see in episodes like What’s My Line or Sense and Sensitivity that Angel feels shame over his vampiric face, and tries to hide it from the people he loves. We get a glimpse of his fears in this episode – his “mask” is revealed when he fights a demon in Buffy’s kitchen, and it is the sight of it that causes Buffy to run away in fear. Despite his best efforts to conceal it, Angel’s “true face” rises to the surface.

Cordelia is special among all these characters, as she is someone nearly incapable of feeling shame. She is at total ease with who she is, and doesn’t need to hide any part of herself. That’s why she is the only character in this episode not affected by any kind of costume or hidden identity. She knows exactly who she is.

We do not get a clean resolution to the Giles question. That’s something for the show to dig into further in a couple of episode’s time. What is clear is that the final shot that this episode leaves us on is a look from Giles – an icy stare into the camera. There is no reason for him to perform in this moment, nobody to wear a costume for. And yet it is absolutely clear that this is not the tea-drinking, excessively British librarian that we have grown so fond of.

This is Ripper.

Part Two: Buffy, Xander, and the Performance of Gender

“What does this mean?”

Willow Rosenberg and Rupert Giles, 2×06 Halloween

“Primarily, the division of self. Male and female, light and dark.”

We open this episode on Buffy fighting a vampire, as another vampire (later, we learn, sent by Spike to study her fighting style), films her. It is an act of vouyerism, of observation. Right away, we are clued into what this episode is about for her: performance. Specifically, the performance of gender.

Buffy goes from this impromptu staking to a date with Angel – the one they planned in Reptile Boy, but finds him already chatting and enjoying himself with Cordelia. This triggers her own insecurity in this episode – her fear that her Slayer destiny will render her unable to correctly perform femininity.

“Dates are things normal girls have. Girls who have time to think about nail polish and facials. You know what I think about? Ambush tactics. Beheading. Not exactly the stuff dreams are made of.”

Buffy Summers, 2×06 Halloween

As mentioned many times before, Buffy is built on this idea of combining two seemingly incompatible archetypes. The pretty, blonde cheerleader slaying demons in high heels and make-up. The designated feminine and designated masculine. Here, Buffy fears that her masculine/Slayer side is less desirable than her feminine/Girl side, and that one threatens the other. She becomes so enamoured with the dress because it represents the perfect performance of femininity – something which is so often denied her by her Slayer duties.

There is something interesting in the fact that the Watcher’s Council – this constant symbol in the show of overreaching patriarchy – holds contradictory expectations of Slayers when it comes to their gender. A common and implied interpretation for why Slayers are always female is that the Watchers believe it allows them to control them more easily. They expect the Slayer to be passive, unobstructive, to perform uncredited and unpaid services without complaint – the perfect Stepford-wife image of docile femininity.

And yet, they also expect them to be fierce, to be strong, to be cold and stoic and form no emotional attachments. To be warriors. They expect Slayers to perform traditional masculinity, as well as traditional femininity. I am reminded of how in the real world, women are both expected to perform femininity in acceptable ways – through the correct dress, correct make-up, correct behaviour – but are simultaneously punished if they are too feminine, and don’t perform masculinity in acceptable ways. They must be feminine, but being too feminine is vain and snobby. We must wear our bows and pretty dresses, but we also must not be above playing in the creek. There is no winning move for women under patriarchy. There is no winning move for Buffy in her struggles here.

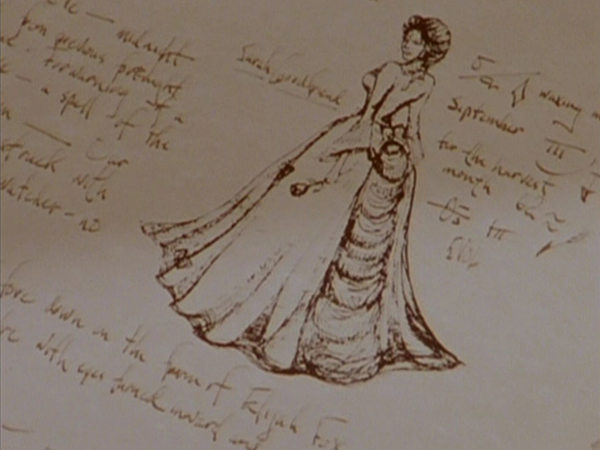

In this part of the episode, Cordelia represents idealised femininity. She can perform in ways that Buffy is unable to – turning up to Buffy’s own date, as she says, “wearing a stunning outfit and embracing personal hygiene”. The girls she sees in the Watcher diaries are the same for her – idealised images of what society expects from women, with perfectly coiffed hair and tiny waists. Both are a threat to Buffy, both in regards to her relationship with Angel, and in her sense of identity. She is both Girl and Slayer, but she sees Cordelia as a more successful version of her Girl side.

“Look, Buffy, you may be hot stuff when it comes to demonology or whatever, but when it comes to dating, I’m the Slayer.”

Cordelia Chase, 2×06 Halloween

There is, of course, nothing wrong with being a feminine woman who enjoys make-up and facials. Buffy is feminine in those traditional ways, and that’s part of her appeal as a trope-breaking heroine. However, in this episode she focuses on it to the point of romanticising the oppressive past. She talks fondly of fantabulous gowns, balls, servants – all the hallmarks of Disneyfied princesshood. She needs Willow to remind her that the present is fairly kinder to women, at least in terms of their ability to vote.

When Buffy transforms into the 18th century noblewoman, she reduces herself. She declares that she “wasn’t meant to think”, and defers entirely to the men around her. In a way, this is a little similar to what Cordelia was saying in Reptile Boy, about laughing at a guy’s jokes and not saying too much about yourself. This icon of successful femininity, as she exists in Buffy’s eyes, is telling her to lessen her own power in order to please a man – and 18th-century-Buffy follows that advice.

Xander is undergoing a similar trial in this episode. His angst is over his inability to effectively perform masculinity. He stands up to Larry when he ‘insults Buffy’s honour’, and attempts to fight him, as he believes is expected of any man. Obviously he is about to get pummeled, and is only saved by Buffy’s physical intervention.

“I’m gonna do what any man would do about it: (grabs Larry by the shirt) somethin’ damn manly.”

Xander Harris, 2×06 Halloween

Xander, in his insecure teenage way, is incensed by this. He is uncomfortable that she is able to perform masculinity more effectively than him. Buffy is to him what Cordelia is to Buffy – an image of competent gender performance that they feel unable to measure up to. Willow connects the ideas when she points out Xander’s fragility, but then immediately switches to asking Buffy about her date – which is an example of Buffy’s own fragile perception of her gender performance. He chooses a military costume because it represents the “correct” performance of masculinity he wants to live up to.

Buffy and Xander are interesting counterparts through this lens, when considering the whole show. Xander is somebody who admires traditional masculinity, and constantly attempts to imitate it, but gradually finds himself more at home in a traditionally feminine narrative role. He is the Heart, the Chick, who saves the day not with the power of his fists, but with the power of love. Buffy admires traditional femininity, but is uncomfortable with that kind of emotional intimacy. She takes up the typically masculine narrative role – the Hero, the Warrior, who leaps to action first and asks questions later. Xander and Buffy both strive towards the masculine and feminine respectively, but through their actions they clearly show themselves to be more skilled in activities deemed appropriate for the opposite gender.

Again, it is entirely valid to be a man who likes typically masculine things/a woman who likes typically feminine things, but it is simultaneously true that society expects men and women to perform these specific roles in certain ways. Their desires do not exist in a vacuum. Buffy and Xander have grown up in an environment that demands specific gender performances, and they have internalised that. The way they have constructed their perception of their own gender is, to paraphrase Judith Butler[1], the result of both subtle and blatant coercions from the society they exist in. Their anxieties in this episode are a result of these coercions.

Both of them choose a costume in this episode that will allow them to inhabit the perfect talisman of their respective genders. Buffy: the beautiful, delicate, extravagant princess gown. Xander: the macho, action-man military gear. Unlike Willow and Giles, who remember who they are, Buffy and Xander forget themselves entirely and become lost within their own costume. This is because they want to become their costumes. They want to perform gender correctly so bad that their own selfhood disappears within it.

It is here that the show starts to expose some of its limited grasp on these issues. Buffy and Xander both become extreme versions of constructed femininity and masculinity, but while Xander becomes a useful asset to the group, if slightly trigger-happy, Buffy becomes entirely useless. Drusilla predicted it when she said that the spell would “make her weak” – her weakness is played up very strongly. She faints at the sight of danger, she struggles to follow basic orders, and she runs out of the house directly into danger. She becomes near-catatonic in response to any kind of threat, and needs to be rescued.

This is intended as a send-up of the “Damsel in Distress” trope, supposed to show how much more capable Buffy is than the passive roles usually written for women in these kinds of stories. However, this is an extremely limited perspective on the issue. It is the Renaissance Disney approach to feminism – where female characters will be allowed to be “strong”, insofar that they effectively exhibit traits that are traditionally considered masculine. They are the Not Like Other Girls heroines, who are admired and desired because they can perform specific masculine activities while also appearing clearly feminine. They are presentable and desirable, and they also play in the creek.

I believe that over the course of all seven seasons, Xander has a subtle and underplayed arc of gradually learning to accept his narrative role as the Heart, and to stop trying so hard to perform an expected version of masculinity. That is not what happens in this episode though. The big climax of his arc, the moment that gives him a “weird sense of closure”, is when he fights and physically overpowers Larry. He wins by effectively performing masculinity.

Buffy’s extreme version of femininity on the other hand, proves useless to the cause. She is unable to fight back against Larry or Spike as she usually would, and she does not offer any useful alternative skills either. This reduction of women from the past as having no function other than to “look pretty”, as Buffy says, is both misogynistic and historically inaccurate. Noblewomen were educators, logisticians, responsible for running the household and managing servants[2]. They may have been skilled in weaving, sewing, musical instruments, or many other skills. This kind of reflexive dismissal of typically feminine skills as useless, while typically masculine skill in war and fighting is deified, is an attitude that pervades television still today, and this is a prime example of it.

The episode is not saying that “women are useless” or anything as insipid as that. We already discussed how effectively Willow takes charge, and Cordelia’s general confidence, and they are fairly typically feminine women. The sexism is subtler than that. It exists in the default, unquestioned assumption that Xander’s extreme performance of masculinity is useful, while Buffy’s extreme performance of femininity is useless. She only wins when she gets her Slayer powers back – her physical strength and warrior instincts. She too wins by effectively performing masculinity.

“I hated the girls back then. Especially the noble women.”

Angel and Buffy Summers, 2×06 Halloween

“You did?”

“They were just incredibly dull. Simpering morons, the lot of them. I always wished I could meet someone… exciting. Interesting.”

In Buffy’s final scene, Angel reassures her that he likes her just the way she is. On the face of it, that’s a fine lesson to learn. She should be allowed to incorporate both her feminine and masculine sides into one cohesive whole. But the way he does it is by denigrating other women. He groups all other girls (including, implicitly, the other symbol of Buffy’s jealousy – Cordelia) together and dismisses them all as “simpering morons”. Buffy is allowed to stand apart as “interesting”, presumably because of her desired masculine qualities. She is raised up, but at the expense of the other girls, who are worthy of Angel’s hatred. It’s the Not Like Other Girls trope again raising its head.

There are many avenues this episode could have delved into. It gestured toward so many about gender performance, and the impossible contradictions of society’s expectation. But it’s own limited perspective, as a 1990s TV show helmed and primarily written by men, holds it back. It is a blinkered look at feminism, and it doesn’t even know it. It ends up re-enforcing some fairly tired ideas, and becomes a lot less interesting than perhaps it could have been. That does not make the episode, or Buffy‘s feminism, worthless. But it does make it a disappointment

* * *

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting me on Ko-Fi!

* * *

References:

[1] Felluga, Dino. “Modules on Butler: On Gender and Sex.” Introductory Guide to Critical Theory.,http://www.purdue.edu/guidetotheory/genderandsex/modules/butlergendersex.html, Accessed 2 Sept 2021.

[2] Webster, Jeremy W. “Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Work in the Eighteenth Century.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 36, no. 3, 2003, pp. 455–459., http://www.jstor.org/stable/30053395. Accessed 2 Sept. 2021.

One thought on “This Is Just My Outfit (Halloween)”