If season one was about placing the basic foundations of the show, then season two is about expanding its scope, and its complexity. It holds a prism up to the light that season one shines on the characters, splitting it into a thousand rays, a thousand ways to look at the show. This is a show that grows like a wild garden, always becoming more complex and intricate, shoots and vines emerging in unexpected places. This isn’t always necessarily good, but it is always interesting.

Though nearly every episode contributes towards this exponential complexity in some way, there are certain ones that I would call tentpoles. Episodes which expand the scope in some way, that take some significant stride towards transforming this show from a fun teen-drama romp with likeable characters, to a serious and complex piece of art, which is also still a fun teen-drama romp. After Prophecy Girl and School Hard, this is the third of those tentpole episodes. This is a quietly stunning installment, which gives ink to a theme that has been sketched into the background so far, and will go on to be perhaps the defining theme of the series: the theme of choice.

This expanding scope is made visible from the opening scene between Angel and Drusilla. We got a little glimpse of it in episode three, but this is when we really start to understand about the strange and twisted dynamic that exists within the infamous family/polycule that fandom has dubbed the “Fanged Four”, or occasionally “The Whirlwind” – the collective term for Darla, Angelus, Drusilla, and Spike. This episode was written in the wake of Interview With The Vampire, remember – it was inevitable that the Buffyverse would dip its toes into its own messed-up homo-erotic, vampiric family unit at some point.

Drusilla reminds us straight away of the complicated familial nature of this group dynamic, as she sings a lullaby that her mother sang to her, to the boy waiting for his own mother. This is the same lullaby she will sing to Darla in the second season of another show, after she re-sires her, therefore becoming her grandmother’s mother. She is then interrupted by Angel – her former lover and metaphorical father, and the man who literally killed her human mother and her vampire grandmother.

Another Darla link is made when Drusilla calls Angel her “dear boy”, a clearly maternal term of endearment, and one that Darla consistently uses for Angelus (to the point that Angel titles an episode after it). Later, we get our first hints of Spike’s jealousy over Angel, and how that relates to Drusilla. The infinitely incestuous nature of the Fanged Four is not fully delved into yet, but this episode splits open this flower, and lets us peek a little inside. Angel attempts to simplify the situation – telling Drusilla and Spike to leave town and never return, nipping that particular story in the bud – but their own backstories make that impossible. He can’t properly threaten Drusilla, because of his own knowledge of what he did to her before. Their pre-existing trauma traps them and ensures more in the future. Given how enjoyable this toxic polycule always is to watch on screen, I’m fairly glad of this.

Angel’s concealment of this trauma (and of this conversation) from Buffy marks the first of many lies and concealed truths that pepper the episode. It seems almost trite to observe that lying is a major theme in an episode called Lie To Me, but here we go anyway: lying is a major theme in this episode. Beyond Angel’s here are Ford’s hidden illness and betrayal of Buffy, Buffy’s attempt to hide her Slayer life from Ford, Willow keeping the group’s suspicions over Ford a secret from Buffy, Jenny keeping the nature of their date a secret from Giles, Giles’ final lies to Buffy in the closing scene. It’s lies all the way down.

An early season one episode might have delivered a fairly well-made but un-challenging story about the problems that lying can cause. But this is the season of expanding complexity, and so the relative merit of lying comes into the discussion. As Angel tells Buffy in a later scene – some lies are necessary.

Giles seems to agree with this, at least in principle. He has always told Buffy of the need to conceal her identity as the Slayer, and he reminds her of that in this episode when he learns that Ford knows about it. There is obvious benefit to a Secret Identity for any superhero, and Buffy sees that too, as she clearly doesn’t intend to let Ford in on it. She elbows Xander when he subtly jokes about Ford not knowing her “darkest secrets”, and after staking a vampire gives him what is probably the weakest and my favourite Blatant Lie[1] in the series.

“Um… uh, there was a, a cat. A cat here, and, um, then there was a-another cat… and they fought. The cats. And… then they left.”

When it transpires that he already knows the truth (specifically telling her that she “doesn’t have to lie”), Buffy admits the benefit of this to Willow. It makes her friendship with him easier, and in a world where Ford doesn’t sell out Buffy for a chance at vampirism, it would hypothetically allow them a stronger bond, just as Buffy has forged with Xander and Willow. But in this universe, Ford’s knowledge of Buffy’s secret allows him to put her and dozens of innocents in mortal danger. The necessity of this particular lie – Buffy’s Secret Identity – is being brought under examination, and shown to have benefits and drawbacks in both directions.

This lie that Angel is telling, however, is clearly self-serving – though sympathetically so. He wants to protect her, to save her the distress of hearing about what he did. However, by withholding this information, he is hiding valuable knowledge from her. As the Slayer, she needs to know that there is an old and dangerous vampire in town (and not dead, as Giles mistakenly informs her). Understanding more about her gives Buffy a tactical advantage in future fights with Drusila (which we do see at the end of the episode, where Buffy uses her knowledge of Spike’s love of Drusilla to save her vampire groupies by holding her hostage. Ultimately, the reason Angel does not want to share the details is because of his own role in them. His lie is built on shame.

It is useful for Buffy that he does eventually share the information, and not just because of what it tells her about Drusilla. It is most useful in what it tells her about Angelus. Because of this, she knows what he is capable of, and how his obsessions with certain women drive him to concentrate all his evil upon them. It is a reminder of Drusilla’s purpose as a potential future Buffy, and in retrospect, a reminder of where the season will go. That is most clear when the camera pans out, showing us a voyeuristic glimpse of Buffy and Angel through the net curtains – a shot that rhymes sickly with one of the most haunting scenes in this season, at the end of Passion.

Buffy pushes him to tell the truth, and he asks if she loves him. Her response exposes something that I think will be very crucial in future discussions of that ever-thorny question in Buffy fandom – can vampires love? We won’t even start looking at those worms now, but we’ll gesture towards the can so that we can keep an eye on it in future episodes.

“I love you. I don’t know if I trust you.”

Buffy Summers, 2×07 Lie to Me

Her response exposes a level of naivety when it comes to the world of love. She is swept up in this epic gothic romance, to the extent that she separates love from trust. This does not indicate a healthy perception of love. A romantic relationship devoid of trust is a horrifying thing to consider. This does not mean that Buffy never trusts or could not trust Angel at other points, but the fact that she doesn’t now, and yet chooses to continue the relationship anyway, shows that she is ready to forgo one of the most essential foundations for a sound relationship, and that is perhaps not something that will help Buffy in this arena.

It makes an interesting contrast to her words in later seasons, which show that she comes to view trust as an essential part of her relationships, and an essential part of love. Buffy’s viewpoint on romance shifts irrevocably over the series, and it all comes back to the trauma she suffers this season, and the way her first love goes so horrifically wrong. It’s much like what we discussed in Reptile Boy, and her complete turnaround on how eager she is to throw herself into a fiery, whirlwind romance. Her outlook in later seasons is shaped to protect herself from the mistakes she feels she makes here.

“I have someone in my life now. That I love. It’s not what you and I had. – It’s very new. You know what makes it new? I trust him. I know him.”

Buffy, talking about Riley, Angel 1×19 Sanctuary

“I have feelings for you. I do. But it’s not love. I could never trust you enough for it to be love.”

Buffy, to Spike, 6×19 Seeing Red

Back in this episode, Angel is still reluctant to share the details, and tells Buffy that she should neither love nor trust him. An understandable emotional reaction, given the walls Angel has built. But, again like the shockingly relevant Reptile Boy, this is an example of Angel dictating to Buffy what she should feel and do, based on his belief that he knows best. And Buffy again pushes back, telling him that she gets to decide what she feels, not him. She insists on her own ability to choose.

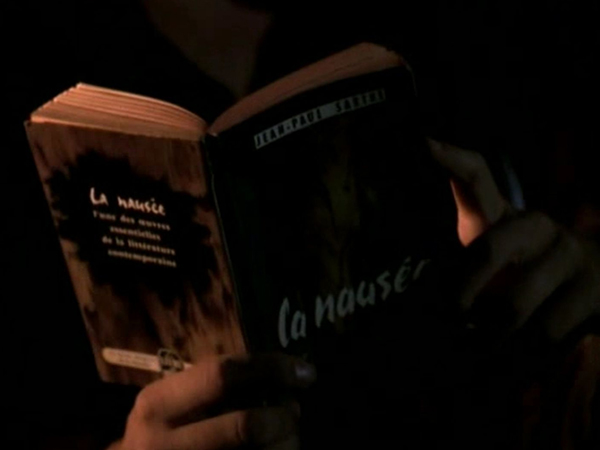

And so, we come to it. Choice. The big theme, the one that, if any single theme could, defines Buffy. As many[2] more[3] intelligent writers have pointed out before me, Buffy is a text that is steeped in the ideas of existentialism and absurdism. Joss Whedon has gone on record saying that La Nausée by Jean-Paul Sartre is one of the most important books he’s ever read, and Albert Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus has received some reference too. Angel is even shown reading the former in Lovers Walk. I am not a philosopher, and I can’t offer any deeper insight into these topics than you can already glean from the aforementioned creators, but it should be acknowledged just how essential they are to the ethical construction of this show.

In a nutshell, existentialism takes as a base assumption a belief that the universe is fundamentally indifferent to human existence. Life, by itself, does not have meaning or purpose, and there is no way to change that. This is the Absurd. But what separates this from depressive nihilism (small n), is the assertion that meaning is created by our own selves. Inside each human exists the freedom of choice, and the choices we make allow us to construct our own meaning. Or, as Angel puts it:

“In the greater scheme or the big picture, nothing we do matters. There’s no grand plan, no big win… If there is no great glorious end to all this, if nothing we do matters, then all that matters is what we do.”

Angel, Angel 2×16 Epiphany

This framework is a constant presence throughout the series. As is made obvious by the constant random death and tragedy that she has to deal with, Buffy lives in a fundamentally uncaring universe. There is no reward for doing good bequeathed upon her by a benevolent god. There’s just life, and all she can do is live it.

Ford attempts to yield himself to the nihilistic dread of an uncaring universe that has left him dying from brain cancer at age seventeen – a horrific and unfair fate for anyone. He claims he has no choice because of this – that he must become a vampire because the alternative is death. This runs counter to the fundamental ideas of existentialism, which are that even in overwhelming circumstances, the individual can never entirely lose their freedom of choice. Even if the choice is “kill or be killed”, you can still choose to be killed. By rejecting this, Ford has made himself an object in the world, at the mercy of its circumstances. Or, as Buffy puts it:

“You have a choice. You don’t have a good choice, but you have a choice.”

Buffy Summers, 2×07 Lie to Me

Ford is not just a failed existentialist here. He is also a failed storyteller. Ford is consistently obsessed with acting out tropes and constructing a narrative around himself. He mouths along to Jack Palance’s Dracula on a television screen behind him. He demands that Spike follow his script and tell him “you’ve got thirty seconds to convince me not to kill you”. He is gleeful when Buffy delivers a line that fits perfectly within his internal screenplay. (“This is so cool! It’s just like it played in my head.”). He constructs a story where he is a tragic yet sympathetic character, who is driven to extreme measures because he has no other alternative.

It is Buffy’s understanding of existentialist principles that allows her to call out this as bullshit, a self-serving narrative that protects Ford from his own agency. She feels sympathy for him, but recognises that he still has a choice, and is actively choosing to harm other people to protect himself. And that is unacceptable to her. So when she gets the innocents out of harm’s way, she doesn’t go back in for him. She lets him die. She makes that choice in full knowledge of the consequences, and lives with it.

“I think this is all part of your little fantasy drama! Isn’t this exactly how you imagined it? You tell me how you’ve suffered and I feel sorry for you. Well, I do feel sorry for you, and if those vampires come in here and start feeding, I’ll kill you myself!”

Buffy Summers, 2×07 Lie To Me

Ford does succeed in writing himself into a story in one way, but it’s not as a tragic hero. It’s as the villain – specifically, as the main villain of season two, Angelus. We are introduced to him as an older guy that Buffy had a crush on, who didn’t date her because she was younger. She tells us that she “moped for months” over him. Already, he is echoing Angel and giving us a jokey glimpse of Buffy’s final state after this season. He becomes the villain in this episode, and finally is killed by Buffy, even as she states sadly that despite everything, she does not hate him. Again, the show echoes forward to Passion, as Buffy and Giles stand together over a grave.

This final scene is beautiful, and sad, and touching of course – but it is also a statement of intent. Buffy ponders on how difficult her life is becoming, how everything in her garden develops increasing, frustrating complexity. Giles tells her that it’s because she’s growing up. That is a fair enough statement, but it’s also talking about the show itself. The show is growing up, becoming more complex, showing us more grey to both heroes and villains, gifting us more pain and death, and it’s not going to let up any time soon. It’s a promise to commit to its own development.

“Yes, it’s terribly simple. The good guys are always stalwart and true, the bad guys are easily distinguished by their pointy horns or black hats, and we always defeat them and save the day! No one ever dies, and everybody lives happily ever after.”

We know that Giles’ final words to Buffy are lies, both in regards to life and to the show. The show we will watch for six more seasons is not simple. The heroes we know now will falter, and fall. The villains will show they can turn to the light. Sometimes, the day is not saved. Our beloved characters will die randomly and meaninglessly, and there is no such thing as happily ever after. We know this, and Buffy knows this too.

And yet, she chooses to be lied to. She acknowledges the truth, but just as in the scene with Angel in the dining room, she defends her right to decide whether or not to hear it. She tells us herself that she is not quite ready to grow up. She’ll get there – just give her time. In this moment, she accepts reality and the horrific indifference of existence – she only asks to be allowed to look away from it, for a moment, and to enjoy a moment of peace. She allows Giles to treat her as a child, as an object. That is what she needs at this moment. That, when all is said and done, is her choice.

* * *

Thanks for reading! I’m going to take a week off to recover from the last couple of lengthy pieces, but will be back on the 30th with the essay for The Dark Age.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting me on Ko-Fi!

* * *

References:

[1] https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/BlatantLies

[2] Passion of the Nerd, Lie to Me – S02E07 – TPN’s Episode Guide, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KiJ7Kscpyks, accessed 14/09/2021

[3] Mark Field, Myth Metaphor and Morality