Part One: The Body

“Sorry, Jenny. This is where you get off.”

There is a moment in the timeline of every piece of media – every show, book, film series, comics run, radio play – where it declares its relationship to death. Sometimes this happens in the opening seconds. You put on an episode of Peppa Pig and you know that this isn’t a show where characters are going to die. You put on Oz and you know that it is. Sometimes it happens in the last few pages of a book that you suddenly realise is going to end with the narrator dying. It can mean the series declaring its gravity: the moment that Eddard Stark loses his head is the moment you realise A Song of Ice and Fire is a series where no character is safe. It can mean the series declaring its triviality: the seventeenth time that the X-Men series resurrects Wolverine will tell its readers not to take any future deaths too seriously.

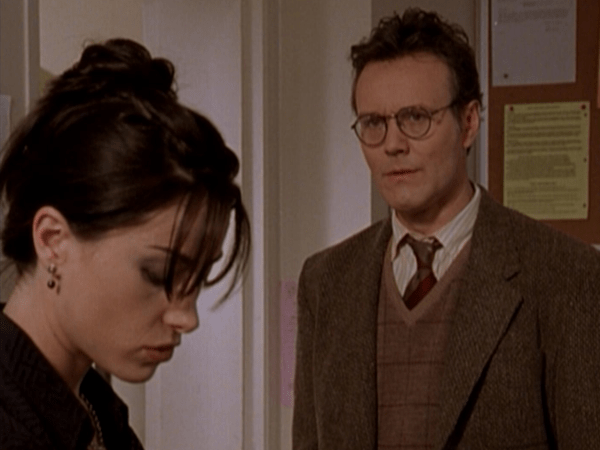

This episode is Buffy’s moment. Jenny is not the first recurring character to die – Principal Flutie and Buffy herself both got there first – but she feels like she is. She sits at the perfect intersection for a character to start fearing their mortality. Important enough to the show for their death to have some weight; not so important that they are effectively immortal. She sits in a little group with Faith and Tara-pre-Seeing-Red – not technically “main characters” given their absence from the title sequences – but considered as main characters by most reasonable people. This ideal combination of importance and unimportance is what dooms her.

From this point on, the audience understands that this is a series where People Can Die. Not anyone, of course – Angel, Spike, and Buffy again all prove too important to suffer permanent deaths. But anyone below that first level in the character hierarchy is fair game, as Joyce, Tara, and Anya will later prove. This is the moment that proves Giles’ lie to Buffy at the end of Lie To Me was, well, a lie. Some people will die. Not everybody will live happily ever after. Least of all Giles.

This episode employs what would go on to become a classic Whedon trick, and perhaps later, a classic Whedon cliche. It raises Jenny’s profile and importance, inviting the audience to see her as becoming indispensable, right before it proves her dispensability.

It’s almost a joke at this point, post Wash, post Fred – to see a happy couple in a Joss Whedon show, because it is the clearest indication that something awful is about to happen to one or both of them. At this point though, for a first-time viewer sitting down in front of their TV 1998 or clutching their season two DVD box set in 2009 or subjecting themselves to a horrific HD release on Disney Plus in 2021, it is a genuine shock. The last two episodes, in the wake of Angel’s turn, have cemented the idea that happiness comes from the secondary romances. Willow and Oz are officially together and progressing their relationship. Xander and Cordelia are back together and progressing their relationship. The first half of this episode is dedicated to repairing Giles’ and Jenny’s relationship, and putting them on course to get back together.

It’s the classic threefold structure that will be familiar to anyone who has ever heard a joke. An Englishman, an Irishman, and a Scotsman walk into a bar. The Englishman says something. The Irishman says something similar but slightly varied. The Scotsman says something apparently similar but unexpected, providing us with a humorous conclusion. 1) Establish Concept. 2) Establish Pattern. 3) Break Pattern. That is what Buffy is doing to us right now, and we fall for it.

As well as the build of the Giles/Jenny romance, the show takes care to weave in parallels between her and Buffy. When she confesses to Giles that she was torn between her duty as she was told it and her love for him, it is the same dilemma that Buffy was facing back in Angel. They are both women stuck between their magical destiny and their love for an older man.

When Buffy tells Jenny to continue feeling guilty and she admits that she will – she is taking instructions from Buffy in more ways than one. Buffy is feeling heavy guilt over Angel’s turn. She’ll feel more at the episode’s end, and even more at the season’s. It is acknowledged that a large part of this guilt is because Buffy was unable to kill Angel, and therefore prevent Jenny’s death. It is unacknowledged but undoubtedly true that another large part of her guilt must stem from the fact that the last thing she said to her was a request to continue feeling bad. Jenny’s promise to do so ensured that she died feeling guilty. That ensures that Buffy will live the rest of her life feeling guilty about that. Like Angel, they are both cursed to eternal, inescapable guilt.

Finally, her plan to re-ensoul Angel provides both a plausible apparent plot direction, and suggests that she might step up her function within the show as a character capable of understanding and performing magic.

The show cleverly hides the fact that this role will be soon taken by another character underneath this suggestion, even as it tells us the truth. Jenny’s research into the ensouling ritual prompts her to ask Willow to cover her class, and it is Willow who will step into this role. It is understated, but Willow actually performs her first spell in this episode – the un-inviting spell on Buffy’s house. Jenny’s research is ultimately what dooms her, allowing Angel to waltz in and kill her at the school, and meaning that Willow will indeed have to step in to cover her classes. With one hand the show is suggesting a more important role for Jenny, while the other is prepping Willow to fill the hole she is about to leave.

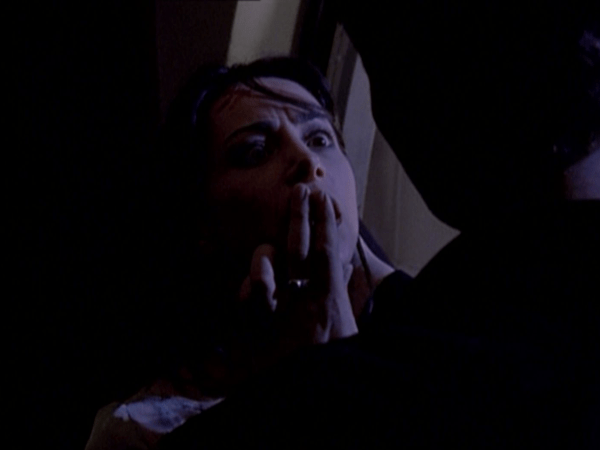

There are two exceptional scenes in this episode that pertain to Jenny’s death. The first is her death itself. It is structured just like most other Buffy fight scenes. The villain enters and makes scary threats. They chase their supposed victim down, being foiled initially but persevering. We don’t know how Jenny will escape yet, but we don’t really suspect her to be in any greater danger than Willow was running away from Oz in Phases, or Xander was when threatened by Angel and Drusilla both in Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered. We have been primed by the way the show has typically gone to expect some sudden intervention – for Buffy to suddenly arrive on the scene and kick Angel’s butt, saving Jenny in the nick of time.

But she doesn’t. Angel catches up with Jenny, in the light of a gorgeously shot window. There is a perfect sick second where we realise, just too late, that no help is coming. This is it. This is where she gets off. This is her exit from the narrative, stage left, quick as you like. This is the end for her. We realise then, that this is a show where people die.

And Jenny dies.

It is perhaps the most significant thing Jenny Calendar ever does. She was a character held up until now just on the sidelines – the most significant character not to make it into the opening credits. She has been constantly just underneath the surface, threatening to break that membrane and become a vital part of the series, but she never quite makes it. She was provided with a potentially rich and fascinating backstory at the last moment, which was completely unplanned and opens up a perverse amount of unanswered questions. Even her death, though vital for its effects on the structure of season two, doesn’t have great ripples outside of this year. She is not explicitly acknowledged at all after season three.

And yet, this moment remains iconic. The shot of Jenny, the window, and Angel snapping her neck with dramatic flourish stays burned into viewers’ minds, and in entering the opening titles becomes part of the fabric of the show itself. Even as she goes unacknowledged, you can read the impact of her death in the emotional states of others. In Buffy’s stubborn, insistent guilt complex. In Xander’s continuing hatred and lack of forgiveness to vampires. In the fact that Giles, after this point, is unique among the Scoobies in never again having any significant love interest. The Doylist reason may be that the cast grew too large and introducing another character to serve as Giles’ love interest may have been seen as unnecessary. The Watsonian explanation suggests very strongly that after Jenny died, Giles was simply unable to ever love anyone else.

Jenny becomes a curious figure in Buffyverse history – the first soldier down, and yet always disappearing into obscurity. She is defined by the reactions of others – in the negative space around her dead body. She does not haunt the narrative. She is amputated from it. She recedes into the aether, the most compelling evidence for her importance provided not by what she left behind, but by what does not rush in to fill the space she left. Jenny has left the building, and now there is only a body.

Part Two: The Gift

“Giles didn’t set this up. Angel did. This is the wrapping for the gift.”

In the last episode, Angel made a promise. He sent Buffy a dozen red roses, and pledged to her a single word: Soon. This promise he kept. It didn’t take long at all for the roses to make a return, as decoration on his piece de resistance – the artfully presented death of Jenny Calendar.

We explored in the previous essay how Angel consistently expresses his affections – however monstrous their form – with gifts and elaborate displays, and that tendency continues here, right from the opening sequence where he gifts Buffy with a beautiful charcoal sketch of her own sleeping face. This episode aired two months after the release of Titanic, which contains within it one of the most iconically romantic scenes of all time, where Leonardo Di Caprio draws Kate Winslet. Angel is repeating that romantic imagery here, but with an overcurrent of darkness and obsession. He draws Buffy like one of his French girls as a threat.

The gifts do not stop coming in this episode. The drawing of Buffy. The drawing of Joyce. Willow’s fish, dead and strung up. Giles designates this behaviour as “battle strategy”, but that is transparently nonsense. Cordelia is entirely correct when she points out that Angel should just slit Buffy’s throat in her sleep. If he was treating this as a battle – as a military engagement – then that would be the objectively correct course of action. To not do that is simply bad tactics, and bad strategy. He is not, of course, treating this as a battle. He’s treating it as a courtship.

Everything that Angel does is intended as a seduction – not in the sense of wanting to win Buffy’s affections, or get her into bed, but to lure her into despair. It is a romantic engagement to him, because death and romance are the same to him. Again, it’s the fresh human heart – romantic imagery intertwined with death, and all of it contained within a single identifiable emotion: passion.

I would be amiss not to mention the sexual undercurrent to Jenny’s murder. He presses his fingers to her lips in an exact mirror of Buffy doing the same to him before their consummation in Surprise, and his final words to her carry in them an obvious double-entendre (“this is where you get off“). It’s not that Angel is gaining sexual pleasure from the murder, it’s that his pleasure is murder. It is the same as sex for him – a flaming passion that drives his actions.

‘Passion’ is an appropriate word to sum up Angel’s behaviour. It evokes not only romance – the kind of fiery whirlwind that Buffy was yearning for in the first half of the season – but also the idea of artistic passions. Angel is an artist. Very literally, in the sense that he draws pictures of Buffy and Joyce, but in his presentation of death. He’s a man of high culture. driven to sculpt his murders into elaborate centrepieces, presented on a bed of champagne, roses, and opera. He’s so obsessed with it he could be a Hannibal villain. He doesn’t find the beauty in death – he believes death itself to be beauty. Death is his passion. Death is his art. Death is his gift.

“Not that it’s any of my business, really, but, uh, what are you planning on conjuring up? If you can decipher the text.”

Shopkeeper and Jenny Calendar, 2×17 Passion

“A present for a friend of mine… His soul.“

Angel’s not the only one giving out gifts. Jenny is his rival here. One of her last acts is a casual gift to Giles – a book that she knows he does not have, which itself calls back to Giles lending her a book in The Dark Age (perhaps this exchange of books is their own kind of love language). Her last is transcribing the ritual to re-ensoul Angel – something she herself describes as a “present” for him. Angel’s soul has been previously described as a “curse”, but here Jenny presents it as something more positive – as a gift. She sees it as a kindness.

If we do consider Angel and Angelus as two separate entities, then re-ensouling him would be akin to killing Angelus, just as Innocence can be seen as a death of a kind for Angel. She is trying to give her own gift of death (and specifically a gift, not a curse). Jenny and Angel are competing bequesters in this episode, but when they go up against each other, there is only one outcome. Jenny loses, and cannot give her gift. Instead, she becomes the gift.

This is the second of the aforementioned two exceptional scenes in this episode. It creates the illusion that Jenny dies twice in this episode – once when Angel snaps her neck, and another when she is found in Giles’ bed. The first comes with shock; the second with the sinking knowledge that the first was no mistake – she really is dead.

This scene is a tour de force, a piece of art from a directorial standpoint as much as it is one from Angel in-universe. From the first shot of the rose on Giles’ front door, from the first haunting note of O soave fanciulla, the audience is imbued with pure dread. This is dramatic irony used for horror. We know that Jenny is dead. We know that Angel has been leaving sick gifts. We know that he can enter Giles’ apartment. And yet, we cannot do anything with this knowledge. We are helpless. We are made slaves to Passion, at the mercy of its circumstances.

It is the same emotion invoked when the audience knows the killer is lurking in just the next room, and we want to scream at the victim ‘no, don’t open that door, the killer is there’, but we know that they will. It’s making the audience unwilling voyuers to a tragedy we cannot stop. It creates the uncomfortable sadness that you might get on a rewatch when you reach the episode where a beloved character dies – but it creates it on a first viewing. We know Giles will find Jenny dead before he does the first time. We want to scream at Giles ‘no, don’t go upstairs, your grief is there’, but we know that he will. Every time, it will play out the same. He will smile at a rose. He will go upstairs. The champagne bottle will smash. Jenny will die. Again, again, again, forever.

We are helpless. Giles is helpless. In the aftermath of this event, he is briefly a broken man – in shock, barely able to string one word after another. He has his own theorem proven somewhat correct – he is indeed thrown off his game by Angel’s “battle strategy”. He stops thinking logically and throws himself into a suicide mission, starting a fight he has no way of winning. He becomes a slave to his anger and grief.

“If we could live without passion, maybe we’d know some kind of peace. But we would be hollow. Empty rooms, shuttered and dank. Without passion, we’d be truly dead.”

Angel, 2×17 Passion

Angel too is helpless. When talking to Joyce, he fakes a reliance on Buffy, telling her that he will “die without [Buffy]”. At least, he pretends to be faking. But it’s true. He is completely and utterly beholden to her. She is the centre of his passions, and his passions are destroying him. He is forgoing the logical option of smothering her in her sleep in order to torture her. He gets called out by Spike for his need to leave “gag gifts” instead of simply killing Jenny cleanly; an act which destroys their home and nearly results in his death. He would be much better off not following his passions, but he can’t do that. To do so would be the end of him.

That’s why he’s telling the truth when he says that he will die without Buffy. He is already a corpse, an unliving creature. Without his passions, he would be nothing. He would be truly dead. He has the luxury of being a slave to them, because he has no other choice. He must give into them, if he is to experience any semblance of life. Amongst all these characters, the only one who doesn’t have this luxury, who is not able to give into her desires, is Buffy.

Part Three: Bargaining

“I can’t hold on to the past anymore. Angel has gone. Nothing’s ever gonna bring him back.”

Buffy has spent the last two episodes in a holding pattern. Since she declared herself unready to kill Angel at the end of Innocence, the series has been in subtle discussion as to whether or not she should. Phases makes a compelling moral argument that Angel should be constrained/re-ensouled rather than killed, while also displaying clearly the consequences of inaction. Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered diverts into a discussion on the nature of love, and ends up concluding that Angel while still “loves” Buffy, it is not in the way he did before, and his love is now making him a direct threat to Buffy and those around her.

If we are to interpret everything that happens in the show as representative of something internal to Buffy’s journey – which we should – then we can interpret the last two episodes as her wrestling with her inability to kill Angel. She is in the ‘bargaining’ stage of grief, constructing arguments as to why Angel might not really be gone, and why she might not actually have to kill him – arguments that have only some basis in reality.

She is like Angel – allowing herself to be a slave to her passion, her love. She has not completely let go of what they once had. In the same scene that Willow points out how Angel has not changed entirely – that Buffy is “still the only thing he thinks about” – Buffy admits that her instincts are still to run to Angel for comfort. Both Buffy and Angel are clinging to what they once had, compelled to desire each other in spite of that impossibility. It’s a pattern with them, and it occurs even when one of them is evil. There is a part of Buffy that still wants Angel back, that wants to let him in.

But she knows she can’t. It’s dangerous to do so – literally to let him into the house, and symbolically to let him into his heart (the sexual metaphor is also obvious here). So she takes the first step to cutting him loose in this episode. As Angel declares his complete dependence on Buffy, she declares her independence from him. She “changes the locks” on her heart. Just as in Ted, she reclaims her domestic space, to protect herself and her mother. As she does so, she reclaims her own emotions and sexual agency.

Of course, that’s only step one. Step two is being ready to actually kill him. She gets there, but only too late.

As mentioned earlier, Jenny is caught between her love and her duty, and so is Buffy. Jenny comes to symbolise that struggle within her. So the final step, to get her ready to kill Angel, is for the symbol of that struggle to die. Jenny dies trying to both repair her relationship with Giles and fulfil her duty of keeping Angel ensouled. She tries to have both love and duty. Her death is the seeming final nail in the coffin of Buffy’s love; the last signpost on her way to duty. There’s no way to have both. She has to choose.

In classic Buffy Summers fashion, she of course blames herself for not choosing earlier. She apologies to Giles, for being torn, for bargaining, for being too slow to act. This is where she lets go of all that. It is the point of no return for her – where she makes the decision to kill Angel. As she says herself, he is not coming back. She accepts that she has already lost him, which in her mind, makes it easier. It means that when she faces him, she would not have anything left to lose.

She’s wrong. She has one more thing.

If Jenny represented the struggle between love and duty, then the disk that stores her last action, her final gift, is a revenant of that struggle. Her conflict becomes her tomb. Giles will not be wrong when in a couple of episodes’ time he comes to suspect that Jenny’s ghost is in the school. This is it. Jenny’s spirit takes the form of a spell on a floppy disk – a more than appropriate fate for a “technopagan”.

Buffy thinks she is ready, that she is done bargaining and has accepted Angel’s death – whether already happened or inevitable at her hand. But hope is a stubborn thing, and does not die so easily. It will come back to haunt her. When she fishes this disk back out in Becoming, the struggle within her will rise like a vengeful spirit, and claim some more lives of those closest to her. The disk is Jenny’s ghost – the ghost of hope – and its effect is to reopen the divide within Buffy between love and duty, the same divide that existed within Jenny.

This is another bait-and-switch that the episode pulls. On first viewing, the shot of the floppy disk seems like a ray of hope, a last light in the darkness, a happy present for the audience. A chance to A gift to us and Buffy. One subsequent viewings, we realise that this light is false, and will only lead Buffy into darker despair, because it will make killing Angel even more traumatising than it already would’ve been. Hope allows her to bargain, and bargaining only makes it harder. This is no gift. This is a haunting. This is a curse.

* * *

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting me on Ko-Fi!

* * *