The test that Buffy undergoes in this episode – in which she is stripped of her powers, locked inside a house, and forced to fight a mentally unstable vampire – is named in the script as The Cruciamentum. Giles describes it as “an archaic exercise in cruelty”, and it’s difficult to think of a description that could be more accurate.

The word Cruciamentum is an invented declension that roughly translates from Latin as “result of torture”. Quentin Travers – making his first appearance here as the Head of the Watcher’s Council – defends the practice as a necessary rite of passage, meant to make a Slayer stronger, but this reasoning falls apart under scrutiny. The scenario is so heavily weighted against the Slayer, robbing her not only of her powers but the knowledge that she is being robbed at all, that it makes more sense to view the Cruciamentum not as a test, but as a method of control, designed to kill off Slayers that reach adulthood and so gain more independence from the Council. At the very least, it demonstrates the Council’s control over the Slayer, holding the implicit threat of taking away her powers again over her head for the rest of her life. As is the case with many unjust systems, the cruelty is the point.

The Cruciamentum is the Council’s most clear and obvious cruelty, but it is not by any means their only one. Cruelty is their origin story, as we see in Get It Done how they forcibly created the first Slayer through metaphorical rape. It is baked into the central idea of One Girl In All The World – a system which relies on the deaths of an infinite chain of young women. Its current setup, with one Watcher in the field and apparently dozens sitting safely away in England, leads to an inevitable cruelty of indifference that Giles calls out in this episode. There are cruelties of incompetence – failing to alert the field about the firing of Gwendolyn Post, sending the underqualified Wesley to Sunnydale. But perhaps their most impactful cruelty is also their most subtle. It came the moment that Buffy Summers, sitting outside her school in 1997, was called to be a Slayer. This act not only changed Buffy’s life, but caused an irreparable crack in her psyche. It splits her perceived self into two component parts – The Girl and The Slayer – twin selves that she spends seven seasons trying to reconcile.

“I have no strength. I have no coordination. I throw knives like…”

Buffy Summers and Rupert Giles, 3×12 Helpless

“A girl?”

“…Like I’m not the Slayer.”

The Girl-Slayer Dichotomy, as we have named it in this essay series, is a concept that underpins the entire series, but it’s always fun when it comes to the forefront of the text, as it does in this episode. The quote above makes the association clear; The Slayer is someone capable of fighting, and The Girl is someone who is not. Losing her slayer powers means Buffy loses the Slayer side of herself, and is rendered simply “a girl”.

It’s striking how terrifying a concept this is for Buffy. Much like in Faith Hope and Trick, the idea of no longer being The Slayer is not an enticing idea for Buffy, as it might have been in seasons one or two, but is now an existential threat. Since identifying herself as ‘Buffy, the Vampire Slayer’ in Anne, the Slayer is now an accepted part of her self-identity. Losing her powers is a classic Flowers for Algernon scenario, as Buffy fears she won’t be able to go back to a “normal” life after having the experiences she has had. But more importantly, she would lose a major part of her identity. Without her Slayer half, Buffy is no longer able to understand who she is.

The result of this is that the original concept of the show – subverting the “young girl gets threatened in an alley by a monster” trope – is un-subverted. A typical Buffy scene of Buffy casually quipping with a vampire she knows she is about to kill falters as Buffy’s powers do, and immediately the power dynamics are switched. The monster becomes threatening as Buffy turns from Confident Hero to Potential Victim. Without the powers of The Slayer, she becomes the horror trope she existed to subvert.

This is perhaps the most classically horror-movie episode of the entire show, with many classic tropes being pulled out. Buffy is stalked down dark streets by a murderer humming an unsettling tune. She is forced to run screaming down the road, begging passing cars to help her. Later she is chased through an abandoned house, and driven into a room that is even more unsettling once she turns on the light. Buffy’s fighting style is no longer athletic and confident, but is desperate and brutal, using every weapon at her disposal to survive. All in all, it’s a pleasingly competent execution of a standard slasher flick. Kralik is the near-unkillable villain in the mold of Ghostface or Michael Myers, while Buffy is the classic Final Girl. It comes as no surprise to any fan of the Scream franchise that Sarah Michelle Gellar is excellent in this role.

The second genre that Helpless pulls from is the genre of fairytale. Buffy is positioned as the titular character of Little Red Riding Hood. Kralik makes two separate references to the story during his pursuit of Buffy. In her first encounter with him, Buffy is literally dressed in a red and hooded coat, and Kralik later uses this coat to trick Joyce into leaving her house, aping the classic Wolf in Grandmother’s clothes. All of this is especially striking coming off the fairytale-centric Gingerbread, and it serves as a reminder that this trope is far older than horror movies. The positioning of young women as victims whose stories centre around being menaced by masculine horrors is an ancient trope as old as misogyny itself.

The theme that ties both these genres together is the threat of sexual violence. Whether it’s Michael Myers penetrating teenagers with knives after they have sex, or the Wolf trying to tempt Little Red Riding Hood away from the forest path, sexual violence and a fear of sexuality in general is an abiding interest of these genres. Having just come off an entire season centred around the dangers of sexuality, Buffy is no stranger to these themes, and sprinkles them liberally through this episode. Both Kralik and the vampire that Buffy first falters against make sexual comments towards Buffy and literally attempt to penetrate her. She is unable to fight back against strangers catcalling her on the street (in a scene reminiscent of Anne, the last time Buffy lost her identity). She can’t protect Cordelia from the ex-boyfriend harassing her. If we view Slayer powers as a general symbol of female empowerment that allows women to fight back against male aggression, then it follows that when robbed of these powers, Buffy immediately finds herself vulnerable to that aggression, and at risk of sexual violence.

Of course, “women need superpowers to be empowered” is a message so transparently un-feminist that even Joss Whedon is smart enough to avoid it. Rather, this is a story about women fighting back without superpowers, and it starts well before Buffy’s inevitable victory at the story’s climax. While Buffy is unable to overpower the boy harassing Cordelia with her (lack of) Slayer powers, Cordelia is able to overpower the boy herself anyway, with no superpowers at all. Later, when Buffy has discovered Giles’ betrayal but knows it isn’t safe for her to walk home alone, it is Cordelia she turns to as her protector, asking her to drive her home. Cordelia has always represented Buffy’s ‘Girl’ side, and when her Slayer side is lost, it is the Girl that becomes the source of protection. Simply put, it’s women-helping-women on the Jungian level.

“Before I was the Slayer, I was… well, I, I don’t wanna say shallow, but… Let’s say a certain person, who will remain nameless, we’ll just call her Spordelia, looked like a classical philosopher next to me.”

Buffy Summers, 3×12 Helpless

Buffy likens herself to Cordelia explicitly, and she frames this as a pure negative. She looks down on the Girl side of herself, and fears that without her Slayer side, that is all that she is. It takes Angel to remind her that her strength predates her Slayer powers, by going back to that first cruelty from the Watchers; the moment they called her and split her psyche in two. This is vital in getting Buffy to the victory she wins at the end of the episode, as she can see through Cordelia and herself that the Slayer is not separate to the Girl, but exists both inside and around it.

Working through his own duality in this episode is our soon-to-be-ex watcher, Rupert Giles. Giles has been on an interesting trajectory this season. We see more of his casual, relaxed side as his relationship with Buffy evolves from a strict hierarchy between adult and child into more of a partnership between adult equals. Simultaneously, Giles’ life is more centred around his Watcher duties than ever before, as since Jenny’s death he is more isolated than ever from any adult companionship outside of Buffy and her friends. This is an unsustainable situation, and so the two opposing forces come into direct conflict here, exposing the duality within Giles.

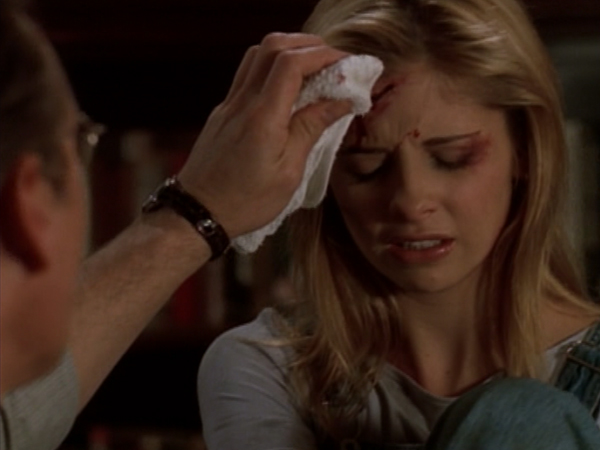

On one side of his psyche, we have the Watcher. The Watcher is concerned with duty, tradition, propriety, and the fight against Evil above all other things. The Watcher is the person who will send Buffy to die in Prophecy Girl, who will drug her in this episode, and who throughout the series will insist that Buffy prioritise her duties as Slayer over any ties to friends, family, lovers, or her wish to have a normal life. On the other side, we have the Father. The Father is all about love, affection, protectiveness, and Buffy’s happiness above all other things. The Father is the person who will attempt to die in Buffy’s place in Prophecy Girl, who will risk his job to get her back in school, who will encourage her to seek a fulfilling life outside of slaying. It’s the Father that comes clean to Buffy in this episode, and tends to her wounds at the story’s end.

This dichotomy maps fairly well onto Buffy’s own. The Watcher exists primarily in relation to the Slayer, in the realm of duty and supernatural power. The Father is linked to the Girl, in the realm of home, hearth and familial love. This link is compounded when Buffy describes her birthday tradition of visiting the ice show with her father – a show she later tries to get Giles to take her to – as a “dumb girly thing”. The problem for Giles is that if the two sides of Buffy exist in harmony, then the two sides of Giles cannot.

We have already mentioned Prophecy Girl, and the scene in which Giles admits his betrayal to Buffy directly parallels the scene in that episode when Buffy realises she is prophesied to die. The scenes are twins in tone and general content, as a tearful Buffy yells at a shamed Giles in the school library, and this follows through to even the composition – as we see Buffy throw an item past Giles to strike the wall in the exact same spot in both scenes. Later, as Buffy goes to face Kralik despite knowing he vastly outpowers her, she wields a crossbow: the same weapon that she brought with her to face her death at the hands of the Master.

These parallels exist to remind us that of the Slayer’s inevitable mortality. Even if we don’t accept the theory that the Cruciamentum is meant to kill off Slayers, that the primary duty of a Watcher is still to encourage Slayers to die. Watchers exist to make sure that Slayers fight evil, and remain fighting evil until their inevitable deaths doing so. No father worthy of the title would send their daughter out to risk their life every night, knowing that their death is both inevitable and soon-coming. In order to keep his title, a Watcher must do this to his Slayer.

“You know, [going to the ice show] is usually something that families do together. If someone were free, they’d take their daughters or their student… or their Slayer.”

Buffy Summers, 3×12 Helpless

On some level, Giles understands this. This is why he pulls away when Buffy makes very obvious overtures towards him taking her to the ice show, and therefore taking on the role of her father. It’s not that he doesn’t want to be her father. He already has the “father’s love” for her that Quentin speaks of at the end of the episode. It’s that being Buffy’s father is incompatible with being her Watcher, and in that moment he is choosing the latter. During this exchange, he asks Buffy to look at the crystal he will use to hypnotise her, and to “look for the flaw at its centre”. He is talking about his own flaws, subconsciously begging her to see him as a messy, illaudable human and not a source of parental admiration. And even more, he is talking about the flaw at the centre of the Slayer/Watcher dynamic, which demands that the Slayer rely entirely upon the Watcher for guidance and support, as a child would a parent, and simultaneously that Watchers send their Slayer-children out to die. Quentin is entirely correct. A Father’s love is, in fact, useless to the Watcher’s cause.

The villain of this episode reveals to Joyce when he has her tied up that he “has a problem with mothers”. But for all Joyce’s faults – and even her attempted murder of Buffy last episode – mothers are pretty blameless here. It is fathers that are, if not outright villains, then at least total disappointments. Buffy is abandoned by one father, and then betrayed by another. She is threatened by Kralik, who wants to turn her into a vampire, and therefore become her morbid ‘father’. The supposed original version of this episode, which emphasised Quentin as a father figure to Giles, would have made this theme a slam-dunk, but it remains present nonetheless, and forms a vital cog in a season that is building to a confrontation with The Mayor: a father figure himself, both personally towards Faith and systematically as a symbol of patriarchal power.

Watcher and Father differ in many ways, but they share common ground in that both are patriarchal figures. They are (typically) male figures of authority presiding over (always) female subjects. Both slayer and daughter are meant to obey, to acquiesce to his will. Buffy rejects the idea of someone else having control over her life, and so she rejects patriarchal authority in all its forms. If both Slayer and Girl are symbols of female empowerment, then both Watcher and Father are incompatible with that empowerment.

So Buffy passes the test, and Giles does not. She is able to unite the two parts of her identity, as doing so emboldens the central themes of the show. Giles cannot unite the two parts of his, as they are symbols of patriarchy, and incompatible with the empowerment of women. His firing comes as a shock, but in truth it was an inevitability. Buffy was always going to have to move past the patriarchal Slayer/Watcher dynamic in order to achieve power as an independent adult. For now, she has had it stripped from her, but as we will see in Graduation Day, it is only a matter of time until she finishes the job.

I absolutely adore reading your essays on buffy after having recently fallen in love with the series! Are you planning on continuing?

LikeLike

I just finished the Zeppo essay today. 🙂

LikeLike

Amazing! Can’t wait to read it once it’s uploaded 🙂

LikeLike